Some great little bits in this exhaustive survey of the evidence (amulets! letters! stelae! votaries!)

'Despite the many positive images of the afterlife, some of the owners of the biographical inscriptions express apprehensions about death. [for example, one says:] "A moment of seeing the rays of the sun is more beneficial than eternity as the ruler of the realm of the dead." ... there was perhaps some questioning of the accepted funerary beliefs and ideas concerning the afterlife...' (p47) I wonder if loads of people did, but it was unwise to express fears about what the afterlife might be like, lest they come to pass.

Talking about the 'fertility figurines' found in peoples' homes and as votive offerings at shrines, naked clay female figurines presumably used to 'bring about conception, ensure a successful pregnancy and protect offspring during childhood', Adderley says: 'The naked female figure may have represented a goddess, either a specific deity (perhaps varying from region to region) or simply a generic divine female... Waraksa has suggested that a generic form may have been used "in order to protect the deity involved from the affliction she was being asked to address."' (p173)

This made me smile. The oracular amuletic decrees, rolled up in a container and worn around the neck, were written guarantees from the gods to protect the wearer from every kind of calamity -- impressive promises of protection against "every kind of illness which is known and every kind of illness which is not known", "every death, every illness and every suffering which comes to people". But just in case, one of them added: "I shall provide [for him] a physician who heals." (My relationship with Sekhmet in a sentence.) (p 199)

The wearer might need protection against not just evil spirits, but malevolent deities, such as Sekhmet, Nefertem, Bastet, 'the fierce lion of Bastet whose sustenance is the blood of people', Ptah, Isis, Horus, Amun, Mut, Khonsu, and Thoth. It's surprising to see these righteous gods in a sort of line-up of potential aggressors against the individual; I suppose someone had to be responsible when bad things happened to people. The decree would promise to propitiate the gods in question. (p 203)

'Despite the many positive images of the afterlife, some of the owners of the biographical inscriptions express apprehensions about death. [for example, one says:] "A moment of seeing the rays of the sun is more beneficial than eternity as the ruler of the realm of the dead." ... there was perhaps some questioning of the accepted funerary beliefs and ideas concerning the afterlife...' (p47) I wonder if loads of people did, but it was unwise to express fears about what the afterlife might be like, lest they come to pass.

Talking about the 'fertility figurines' found in peoples' homes and as votive offerings at shrines, naked clay female figurines presumably used to 'bring about conception, ensure a successful pregnancy and protect offspring during childhood', Adderley says: 'The naked female figure may have represented a goddess, either a specific deity (perhaps varying from region to region) or simply a generic divine female... Waraksa has suggested that a generic form may have been used "in order to protect the deity involved from the affliction she was being asked to address."' (p173)

This made me smile. The oracular amuletic decrees, rolled up in a container and worn around the neck, were written guarantees from the gods to protect the wearer from every kind of calamity -- impressive promises of protection against "every kind of illness which is known and every kind of illness which is not known", "every death, every illness and every suffering which comes to people". But just in case, one of them added: "I shall provide [for him] a physician who heals." (My relationship with Sekhmet in a sentence.) (p 199)

The wearer might need protection against not just evil spirits, but malevolent deities, such as Sekhmet, Nefertem, Bastet, 'the fierce lion of Bastet whose sustenance is the blood of people', Ptah, Isis, Horus, Amun, Mut, Khonsu, and Thoth. It's surprising to see these righteous gods in a sort of line-up of potential aggressors against the individual; I suppose someone had to be responsible when bad things happened to people. The decree would promise to propitiate the gods in question. (p 203)

Haven't written up a subject: sex and gender posting about alternative genders in forever, so let's have a few notes on the sadhin of the Himalayan foothills. "A sadhin can take on many of a man's social roles and behavioural attributes, can wear men's clothes and can cut her hair short like a man. Becoming a sadhin is regarded as a respectable alternative to marriage for a female." The sadhin, who remains female, adds the suffix Devi to her name. Shaw points out that a man can become an ascetic at any time in his life, while the sadhin takes on her role only at puberty.

More on the sadhin here:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3630617

Phillimore, Peter. Unmarried Women of the Dhaula Dhar: Celibacy and Social Control in Northwest India. Journal of Anthropological Research. Vol. 47, No. 3 (Autumn, 1991), pp. 331-350 (20 pages)

ETA: In turn, Phillimore mentions this article, about the transgender jogamma ("male, ascetic women"), disciples of the goddess Yellamma:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3629673

Bradford, Nicholas J. Transgenderism and the Cult of Yellamma: Heat, Sex, and Sickness in South Indian Ritual. Journal of Anthropological Research Vol. 39, No. 3 (Autumn, 1983), pp. 307-322 (16 pages)

__

Alison Shaw and Shirley Ardener (eds). "An Introduction." in Changing Sex and Bending Gender. Berghahn Books, New York; Oxford, 2005.

More on the sadhin here:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3630617

Phillimore, Peter. Unmarried Women of the Dhaula Dhar: Celibacy and Social Control in Northwest India. Journal of Anthropological Research. Vol. 47, No. 3 (Autumn, 1991), pp. 331-350 (20 pages)

ETA: In turn, Phillimore mentions this article, about the transgender jogamma ("male, ascetic women"), disciples of the goddess Yellamma:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3629673

Bradford, Nicholas J. Transgenderism and the Cult of Yellamma: Heat, Sex, and Sickness in South Indian Ritual. Journal of Anthropological Research Vol. 39, No. 3 (Autumn, 1983), pp. 307-322 (16 pages)

__

Alison Shaw and Shirley Ardener (eds). "An Introduction." in Changing Sex and Bending Gender. Berghahn Books, New York; Oxford, 2005.

A hiatus for the Book of the Dead

Dec. 27th, 2023 09:24 pm"The Book of the Dead was used throughout the New Kingdom and Twenty-first Dynasty, and then, following an apparent hiatus in its use in the Twenty-second and Twenty-third Dynasties, from around 700 BCE to Ptolemaic times." -- Nicola J. Adderley, Personal Religion in the Libyan Period in Egypt, p 42 n211 (which leads to:)

"In the ninth century BC the detailed decoration of Theban coffins gave way to a plainer style without texts and the local practice of placing funerary manuscripts in he burial vanished altogether. At Tanis in the north meanwhile we find for the first time since Ramses XI royal burial chambers inscribed with scenes and texts extracted from the Book of the Dead and the Underworld Books. The occurrence of both startling reversals in the surviving record at the two governing centres of Egypt suggests that there may be a link to wider historical developments; the reign of Osorkon II brought a reimposition of northern control over Thebes, which resisted with force according to the Karnak inscription of the general Osorkon, a prince in the royal house. Yet the link may not amount to a direct royal clampdown on Theban use of texts because the Thebans did not resume their earlier coffin and manuscript traditions under the weak successors of Osorkon II. It is also significant that the disappearance of funerary texts involved not only those reserved before 1100 BC for the king but also.the Book of the Dead which had always been available to his subjects. Therefore the renewed vigour of the north under Osorkon II may have caused the change in Theban burial customs more indirectly, by promoting the spread of northern textless funerary traditions to the southern city, much as funerary customs altered abruptly in the nineteenth century BC without any obvious political motivation.

"Whatever the reasons for the change, for over a century no funerary literature survives..." -- Stephen Quirke, Ancient Egyptian Religion, pp 167-8

__

Nicola J. Adderley. Personal Religion in the Libyan Period in Egypt. OmniScriptum, Saarbrücken, Germany, 2015.

Stephen Quirke. Ancient Egyptian Religion. British Museum Press, London, 1992.

"In the ninth century BC the detailed decoration of Theban coffins gave way to a plainer style without texts and the local practice of placing funerary manuscripts in he burial vanished altogether. At Tanis in the north meanwhile we find for the first time since Ramses XI royal burial chambers inscribed with scenes and texts extracted from the Book of the Dead and the Underworld Books. The occurrence of both startling reversals in the surviving record at the two governing centres of Egypt suggests that there may be a link to wider historical developments; the reign of Osorkon II brought a reimposition of northern control over Thebes, which resisted with force according to the Karnak inscription of the general Osorkon, a prince in the royal house. Yet the link may not amount to a direct royal clampdown on Theban use of texts because the Thebans did not resume their earlier coffin and manuscript traditions under the weak successors of Osorkon II. It is also significant that the disappearance of funerary texts involved not only those reserved before 1100 BC for the king but also.the Book of the Dead which had always been available to his subjects. Therefore the renewed vigour of the north under Osorkon II may have caused the change in Theban burial customs more indirectly, by promoting the spread of northern textless funerary traditions to the southern city, much as funerary customs altered abruptly in the nineteenth century BC without any obvious political motivation.

"Whatever the reasons for the change, for over a century no funerary literature survives..." -- Stephen Quirke, Ancient Egyptian Religion, pp 167-8

__

Nicola J. Adderley. Personal Religion in the Libyan Period in Egypt. OmniScriptum, Saarbrücken, Germany, 2015.

Stephen Quirke. Ancient Egyptian Religion. British Museum Press, London, 1992.

Die "Herrin der Unterwelt"

Dec. 2nd, 2023 01:31 pmI stumbled through this German-language article with the help of Google translate, which was very gentle about the umlauts. It's about Hepet-Hor, but refers to her by one of the other epithets she's given, "Mistress of the Duat".

The goddess has various headdresses -- a cobra, an atef crown, a feather. In one example, she's given the name Neith; in another, Selkis; in still another Saryt. Refai suggests this could be explained by "special devotion or local ties". Hepet-Hor also appears as one of the gods in the Litany of Re.

Here's Google Translate's attempt at a key passage: "The exact nature and function of this underworld goddess remain difficult to interpret. In the variation of her representations, she shows several arbitrary combinations, which include protection symbols (knives, lions) on the one hand and symbols of regeneration (snakes, crocodiles) on the other. As is often the case, it combines protection and regeneration, the two most important afterlife hopes of the deceased." Her "embracing" is protective. IIUC, in a couple of papyri, Hepet-Hor's function is clear: she welcomes the deceased to the underworld. In some inscriptions she offers bread, beer, and "all good things" to the deceased, which reinforces this idea. Refai states that "The goddess certainly forms a partial aspect of the personified underworld kingdom from which the deceased hopes for reception, protection and regeneration."

__

Refai, Hosam. Die "Herrin der Unterwelt". in Ursula Rössler-Köhler et al (eds). Die Ihr Vorbeigehen Werdet. Berlin, New York, Walter de Gruyter, 2009.

With this and other epithets, a curious female figure appears on papyri and coffins of the Late Period, who apparently has an important, yet difficult to interpret, underworldly function. Her depiction remains unchanged, apart from variations in the shape of her head and the inscription. She is shown standing wearing a tight, long robe and holding a knife in both hands. There is often a sacrificial table in front of her, and in some examples Thoth presents her with a Western symbol.

Although Hepet-Hor's head and title/name change, she always wears one of those sheer dresses and has a knife in either hand. (I wonder if this helps to differentiate her from similar double-headed goddesses who don't have the knives - eg Niwinski fig. 25) She most often has the head of a snake, and most often appears in front of the double staircase / primordial mound / step pyramid thing, borne on the back of the great serpent, where Osiris is enthroned. She also sometimes appears at the judgement.The goddess has various headdresses -- a cobra, an atef crown, a feather. In one example, she's given the name Neith; in another, Selkis; in still another Saryt. Refai suggests this could be explained by "special devotion or local ties". Hepet-Hor also appears as one of the gods in the Litany of Re.

Here's Google Translate's attempt at a key passage: "The exact nature and function of this underworld goddess remain difficult to interpret. In the variation of her representations, she shows several arbitrary combinations, which include protection symbols (knives, lions) on the one hand and symbols of regeneration (snakes, crocodiles) on the other. As is often the case, it combines protection and regeneration, the two most important afterlife hopes of the deceased." Her "embracing" is protective. IIUC, in a couple of papyri, Hepet-Hor's function is clear: she welcomes the deceased to the underworld. In some inscriptions she offers bread, beer, and "all good things" to the deceased, which reinforces this idea. Refai states that "The goddess certainly forms a partial aspect of the personified underworld kingdom from which the deceased hopes for reception, protection and regeneration."

__

Refai, Hosam. Die "Herrin der Unterwelt". in Ursula Rössler-Köhler et al (eds). Die Ihr Vorbeigehen Werdet. Berlin, New York, Walter de Gruyter, 2009.

Part one of my notes

I'm up to the papyri I'm most interested in -- the ones Niwiński calls "the new redaction [of the Book of the Dead] of the 21st Dynasty", ie the ones with all the strange new imagery. So I thought I'd start a new posting.

(p 132) Niwiński divides them into groups, starting with "the figural hieroglyphic papyri":

- more pictures than text

- the etiquette's on the right; you read the scroll right to left.

- the writing's in hieroglyphs (as opposed to hieratic), arranged in vertical columns

- the etiquette and vignettes, and often the border, are coloured

- the content is mostly chapters of the Book of the Dead, but there are new illustrations invented at the start of the 21st Dynasty

- included a limited repertoire of BD spells (some taking on the function of others, some changed)

"... among those belonging to the subtype under discussion, several "families", or groups of the papyri of analogous contents can be distinguished, being probably reflection of the origin of these papyri from the same workshop, where the same patterns of texts and scenes were used." That's extraordinary -- we're almost down to the individual artist here. I wonder where the new patterns came from? Perhaps a master artisan said, right, this is what we're doing now? Maybe after discussions with a priest?

The judgement scene (BD 125, and also representing BD 30B) is the most common scene on Niwiński's papyri, often accompanied by BD 126. (I'm confess I don't know my BD chapters very well so I'm going to have to look some of this up. Can't wait for more libraries to have The Oxford Handbook to the Book of the Dead). There's a new scene of purification, called BD 195, on many papyri, and many have BD 149/150. BD 186, the Hathor-cow emerging from the mountain, is popular on papyri and coffins (p 140). Rituals are sometimes represented (p 143).

(p 139) "The creativity of the Theban artists of the period expressed itself in a great number of figural variations of the same theme, each papyrus being, practically, a unique combination of the motives, even within the same family', or series of papyri." In the judgement scene, Osiris can be replaced by the sun-god.

As well as variations on chapters from the Book of the Dead and other afterlife books, there were new theological compositions, such as the scene with Geb lying beneath Nut (p 147). In a small number of cases, scenes from the Amduat crop up on a papyrus titled "Book of the Dead" and vice versa (p 150).

(p 151) This type of papyrus first appears at the start of the 21st Dynasty and is in full swing by the middle, until the end of the reign of the High Priest Pinudjem II. There are still "sporadic" examples after this, but they've disappeared by the 22nd Century.

The next subcategory of papyrus Niwiński considers (p 152) is similar to the above, but:

- in black ink only, with occasional use of red

- quality of the drawings varies

- many more pictures than text

- probably got started under the High Priest Menkheperre and went until the end of the 21st Dynasty

(Fig 45 is the bizarre version of Osiris that got this whole obsession going. I love all this crazy post-New Kingdom iconography, the crazier the better. You get so used to the staid, traditional representations in coffee table books, and then bam, Osiris has a donkey's head and Sekhmet is a hedgehog.)

Niwiński puts the papyrus of Nesitanebetasheru (aka the Greenfield Papyrus) into its own category, with 87 chapters of the Book of the Dead and lots of extra hymns etc, written in hieratic, all illustrated in black ink.

Almost all of the other papyri Niwiński considered have the Amduat. Some have just the last four hours of the book, some include content from the Book of the Dead, and some have contents closer to the Litany of Re, even though they're entitled the Amduat.

The Amduat starts out in royal tombs, as does the Litany of Re. Amduat papyri for private individuals were introduced at the start of the 21st Dynasty, or the end of the 20th, in what Niwiński calls "the Renaissance Era under Ramesses XI and the HP Herihor". Mummies were usually buried with two papyri, a Book of the Dead and an Amduat (but sometimes it's only the title that tells you which is which -- p 236).

Niwiński groups the Amduat papyri into four main groups:

- the ones that resemble the Litany of Re (and perhaps BD 168)

- the more traditional ones, closer to those found in royal tombs

- the ones that resemble the Book of the Dead

- the bonkers ones (my favourite)

The first group, the Litany of Re-like papyri, are divided into many panels, each one containing one form of the "united Osirian-solar aspects of the Great God", each one labelled with that form's name. These appeared while Herihor was High Priest and disappeared under Pinudjem II. There are also two papyri which have, as well as the catalogue of the forms of the Great God, "additional iconographic representations".

The next group is based on the Amduat as it appears in royal tombs. Typically there's the etiquette at right, then the last four hours of the Amduat, read left to right, so that the 12th hour is up against the etiquette. The papyri are illustrated in black and maybe red. They first appear in the middle of the 21st Dynasty.

There's a variation where, instead of the normal 3 registers, the figures are laid out in 1 or 2 registers, presumably because the papyrus was too small! The content of these may be "transformed under the influence of other iconographic compositions, and owing to an individual artistic invention of the drawer." Another variation from the late 21st Dynasty is short, usually lacking the etiquette; the four hours are represented by a few figures each.

Next up are the papyri which include motifs from both the Amduat and the Book of the Dead -- how much from each varies from papyrus to papyrus. Ideally, mummies were buried with a BD (in a papyrus sheath) and an Amduat (wrapped with the mummy -- p 213), so even if there were Book of the Dead content, the papyrus must have still been seen as an Amduat. On the other hand, for some burials such as those with only one papyrus, they might have played the role of both texts at once.

The last group comprises papyri which include stuff from the Amduat, the Book of the Dead, and other compositions as well, such as the Book of Caverns, Book of Gates, and Book of the Earth. One subgroup of similar papyri have the deceased worshipping a series of figures from the BD (p 192-3). There's a tendency to cram as much stuff onto the papyrus as possible -- figures, symbols, etc. The figures are often transformed from their original appearance, and new scenes invented by the 21st Dynasty artists appear. This group includes the papyri sometimes called mythological papyri, although Niwiński argues against using this term. Similarities between some of the papyri suggest that the same artist would prepare both of the papyri for the same burial. OTOH sometimes there is a "striking contrast" between them (p 214).

A few bits and pieces:

(p 219) "Poor people buried without coffins or papyri could only rely on the magical protection furnished by the religious texts and representations on papyri and coffins belonging to other deceased persons lying in the same tomb-cachette."

(p 220) The decorations on coffins were an extension of the papyri -- they didn't duplicate their contents. eg Sutimes' outer coffin has the Litany of Re type figures, instead of the expected papyrus (though there's a bit of repetition of the BD stuff on the inner coffin, eg the Weighing of the Heart scene). In the late 21D/early 22D there was more duplication.

(p 236) The fact that papyri vary so widely in quality indicates that you didn't have to be high-status and rich to be entitled to a funerary papyrus.

(p 237) In the 22nd Dynasty the papyri soon settle down into hieratic BD without pictures and traditional Amduats. In turn the Amduat papyri disappear some time during the later Third Intermediate Period.

Good grief, I'm finished!

Andrzej Niwiński. Studies on the Illustrated Theban Funerary Papyri of the 11th and 10th Centuries BC. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 86. Göttingen, Vandenhoeck u. Ruprecht, 1989.

I'm up to the papyri I'm most interested in -- the ones Niwiński calls "the new redaction [of the Book of the Dead] of the 21st Dynasty", ie the ones with all the strange new imagery. So I thought I'd start a new posting.

(p 132) Niwiński divides them into groups, starting with "the figural hieroglyphic papyri":

- more pictures than text

- the etiquette's on the right; you read the scroll right to left.

- the writing's in hieroglyphs (as opposed to hieratic), arranged in vertical columns

- the etiquette and vignettes, and often the border, are coloured

- the content is mostly chapters of the Book of the Dead, but there are new illustrations invented at the start of the 21st Dynasty

- included a limited repertoire of BD spells (some taking on the function of others, some changed)

"... among those belonging to the subtype under discussion, several "families", or groups of the papyri of analogous contents can be distinguished, being probably reflection of the origin of these papyri from the same workshop, where the same patterns of texts and scenes were used." That's extraordinary -- we're almost down to the individual artist here. I wonder where the new patterns came from? Perhaps a master artisan said, right, this is what we're doing now? Maybe after discussions with a priest?

The judgement scene (BD 125, and also representing BD 30B) is the most common scene on Niwiński's papyri, often accompanied by BD 126. (I'm confess I don't know my BD chapters very well so I'm going to have to look some of this up. Can't wait for more libraries to have The Oxford Handbook to the Book of the Dead). There's a new scene of purification, called BD 195, on many papyri, and many have BD 149/150. BD 186, the Hathor-cow emerging from the mountain, is popular on papyri and coffins (p 140). Rituals are sometimes represented (p 143).

(p 139) "The creativity of the Theban artists of the period expressed itself in a great number of figural variations of the same theme, each papyrus being, practically, a unique combination of the motives, even within the same family', or series of papyri." In the judgement scene, Osiris can be replaced by the sun-god.

As well as variations on chapters from the Book of the Dead and other afterlife books, there were new theological compositions, such as the scene with Geb lying beneath Nut (p 147). In a small number of cases, scenes from the Amduat crop up on a papyrus titled "Book of the Dead" and vice versa (p 150).

(p 151) This type of papyrus first appears at the start of the 21st Dynasty and is in full swing by the middle, until the end of the reign of the High Priest Pinudjem II. There are still "sporadic" examples after this, but they've disappeared by the 22nd Century.

The next subcategory of papyrus Niwiński considers (p 152) is similar to the above, but:

- in black ink only, with occasional use of red

- quality of the drawings varies

- many more pictures than text

- probably got started under the High Priest Menkheperre and went until the end of the 21st Dynasty

(Fig 45 is the bizarre version of Osiris that got this whole obsession going. I love all this crazy post-New Kingdom iconography, the crazier the better. You get so used to the staid, traditional representations in coffee table books, and then bam, Osiris has a donkey's head and Sekhmet is a hedgehog.)

Niwiński puts the papyrus of Nesitanebetasheru (aka the Greenfield Papyrus) into its own category, with 87 chapters of the Book of the Dead and lots of extra hymns etc, written in hieratic, all illustrated in black ink.

Almost all of the other papyri Niwiński considered have the Amduat. Some have just the last four hours of the book, some include content from the Book of the Dead, and some have contents closer to the Litany of Re, even though they're entitled the Amduat.

The Amduat starts out in royal tombs, as does the Litany of Re. Amduat papyri for private individuals were introduced at the start of the 21st Dynasty, or the end of the 20th, in what Niwiński calls "the Renaissance Era under Ramesses XI and the HP Herihor". Mummies were usually buried with two papyri, a Book of the Dead and an Amduat (but sometimes it's only the title that tells you which is which -- p 236).

Niwiński groups the Amduat papyri into four main groups:

- the ones that resemble the Litany of Re (and perhaps BD 168)

- the more traditional ones, closer to those found in royal tombs

- the ones that resemble the Book of the Dead

- the bonkers ones (my favourite)

The first group, the Litany of Re-like papyri, are divided into many panels, each one containing one form of the "united Osirian-solar aspects of the Great God", each one labelled with that form's name. These appeared while Herihor was High Priest and disappeared under Pinudjem II. There are also two papyri which have, as well as the catalogue of the forms of the Great God, "additional iconographic representations".

The next group is based on the Amduat as it appears in royal tombs. Typically there's the etiquette at right, then the last four hours of the Amduat, read left to right, so that the 12th hour is up against the etiquette. The papyri are illustrated in black and maybe red. They first appear in the middle of the 21st Dynasty.

There's a variation where, instead of the normal 3 registers, the figures are laid out in 1 or 2 registers, presumably because the papyrus was too small! The content of these may be "transformed under the influence of other iconographic compositions, and owing to an individual artistic invention of the drawer." Another variation from the late 21st Dynasty is short, usually lacking the etiquette; the four hours are represented by a few figures each.

Next up are the papyri which include motifs from both the Amduat and the Book of the Dead -- how much from each varies from papyrus to papyrus. Ideally, mummies were buried with a BD (in a papyrus sheath) and an Amduat (wrapped with the mummy -- p 213), so even if there were Book of the Dead content, the papyrus must have still been seen as an Amduat. On the other hand, for some burials such as those with only one papyrus, they might have played the role of both texts at once.

The last group comprises papyri which include stuff from the Amduat, the Book of the Dead, and other compositions as well, such as the Book of Caverns, Book of Gates, and Book of the Earth. One subgroup of similar papyri have the deceased worshipping a series of figures from the BD (p 192-3). There's a tendency to cram as much stuff onto the papyrus as possible -- figures, symbols, etc. The figures are often transformed from their original appearance, and new scenes invented by the 21st Dynasty artists appear. This group includes the papyri sometimes called mythological papyri, although Niwiński argues against using this term. Similarities between some of the papyri suggest that the same artist would prepare both of the papyri for the same burial. OTOH sometimes there is a "striking contrast" between them (p 214).

A few bits and pieces:

(p 219) "Poor people buried without coffins or papyri could only rely on the magical protection furnished by the religious texts and representations on papyri and coffins belonging to other deceased persons lying in the same tomb-cachette."

(p 220) The decorations on coffins were an extension of the papyri -- they didn't duplicate their contents. eg Sutimes' outer coffin has the Litany of Re type figures, instead of the expected papyrus (though there's a bit of repetition of the BD stuff on the inner coffin, eg the Weighing of the Heart scene). In the late 21D/early 22D there was more duplication.

(p 236) The fact that papyri vary so widely in quality indicates that you didn't have to be high-status and rich to be entitled to a funerary papyrus.

(p 237) In the 22nd Dynasty the papyri soon settle down into hieratic BD without pictures and traditional Amduats. In turn the Amduat papyri disappear some time during the later Third Intermediate Period.

Good grief, I'm finished!

Andrzej Niwiński. Studies on the Illustrated Theban Funerary Papyri of the 11th and 10th Centuries BC. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 86. Göttingen, Vandenhoeck u. Ruprecht, 1989.

Left eye, right eye

Oct. 31st, 2023 10:09 pmHere's a helpful snippet. Discussing this amulet, Dr Carol Andrews remarks on the frequent confusion between the lunar left eye and the solar right eye in Egyptian representations. She notes that the lion is lying in the same unusual position as the two Prudhoe Lions in the British Museum.

"The lion on the amulet is identical to the Prudhoe lion which would have stood on the left. It is known that the pair from Soleb represented the eyes of the sun-god, both solar and lunar, and so the lion on the left might be assumed to represent the lunar eye, the entity which the fierce lion-headed goddesses and, in particular, Tefnut embodied. Yet the amulet has been shown to be a right eye. However, texts exist which show that the right and left eyes might be transposed, as for example, Chapter 151 of the Book of the Dead (Allen: 1974, 147): ‘Thy right eye is the night bark, thy left eye is the day bark.’ Perhaps this explains the presence of a lunar manifestation on a right, solar eye." (my emphasis)

I've been confused by this inconsistency a number of times; apparently even the Egyptians got mixed up.

__

Carol Andrews. "A Most Uncommon Amulet". in Price, Campbell et al (eds). Mummies, Magic and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Multidisciplinary Essays for Rosalie David. Manchester University Press, 2016.

"The lion on the amulet is identical to the Prudhoe lion which would have stood on the left. It is known that the pair from Soleb represented the eyes of the sun-god, both solar and lunar, and so the lion on the left might be assumed to represent the lunar eye, the entity which the fierce lion-headed goddesses and, in particular, Tefnut embodied. Yet the amulet has been shown to be a right eye. However, texts exist which show that the right and left eyes might be transposed, as for example, Chapter 151 of the Book of the Dead (Allen: 1974, 147): ‘Thy right eye is the night bark, thy left eye is the day bark.’ Perhaps this explains the presence of a lunar manifestation on a right, solar eye." (my emphasis)

I've been confused by this inconsistency a number of times; apparently even the Egyptians got mixed up.

__

Carol Andrews. "A Most Uncommon Amulet". in Price, Campbell et al (eds). Mummies, Magic and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Multidisciplinary Essays for Rosalie David. Manchester University Press, 2016.

Arsinoe II

Oct. 31st, 2023 12:27 pmMore photocopies lying around the place.

Žabkar, Louis V. Hymns to Isis in her temple at Philae. Hanover, NH. Published for Brandeis University Press by University Press of New England, 1988.

"It is true that there exist in Egyptian history some well-known examples of the deification and cult of the queen; such names as Teti-Sheri, grandmother of Ahmose, Ahmes-Nefertari, his wife, and Nefertari, chief wife of Ramesses II, immediately come to mind. The fact remains, however, that the divine status of Arsinoë as a co-templar, or temple-sharing goddess, or synnaos theos, closely associated with or assimilated to Isis, was emphasized and displayed at Philae in an unprecedented manner." (More about Arsinoë's deification.)

Céline Marquaille, in her chapter "The Foreign Policy of Ptolemy II", states that Ptolemy used Arsinoe to embody his naval power, creating a goddess "Arsinoe-Aphrodite-Kypris" (Aphrodite of Cyprus) and Arsinoe-Aphrodite-Kypris-Zephyritis, "the protector of seafarers and of Greek maidens about to enter marriage."

Stefan Pfeiffer, in his chapter "The God Serapis" in the same work, notes that "Arsinoe had received her own temple at the Cape of Zephyrion [I suppose this is arsinoe-aprodite-kypris-zephritis?] and, there, became the patron goddess of seafaring as Aphrodite-Arsinoe." (399)

Ptolemy II "elevated her after her death to the temple-sharing goddess of all Egyptian temples. An Egyptian goddess had now emerged from the Greek goddess Arsinoe, appearing in a completely Egyptian form on the temple reliefs and votive steles." Her cult was particular important in Memphis. She may also have a been a temple-sharing goddess in Greek temples. Isis and Aphrodite were equated, and Arsinoe was linked to them both. Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II were both temple-sharing gods for Serapis. (401)

(I had this mad plan to write a novel about Arsinoe II. Could still happen.)

___

Céline Marquaille. "The Foreign Policy of Ptolemy II". in McKechnie, Paul; Guillaume, Philippe (eds). Ptolemy II Philadelphus and his world. Leiden, Brill, 2008.

Žabkar, Louis V. Hymns to Isis in her temple at Philae. Hanover, NH. Published for Brandeis University Press by University Press of New England, 1988.

"It is true that there exist in Egyptian history some well-known examples of the deification and cult of the queen; such names as Teti-Sheri, grandmother of Ahmose, Ahmes-Nefertari, his wife, and Nefertari, chief wife of Ramesses II, immediately come to mind. The fact remains, however, that the divine status of Arsinoë as a co-templar, or temple-sharing goddess, or synnaos theos, closely associated with or assimilated to Isis, was emphasized and displayed at Philae in an unprecedented manner." (More about Arsinoë's deification.)

Céline Marquaille, in her chapter "The Foreign Policy of Ptolemy II", states that Ptolemy used Arsinoe to embody his naval power, creating a goddess "Arsinoe-Aphrodite-Kypris" (Aphrodite of Cyprus) and Arsinoe-Aphrodite-Kypris-Zephyritis, "the protector of seafarers and of Greek maidens about to enter marriage."

Stefan Pfeiffer, in his chapter "The God Serapis" in the same work, notes that "Arsinoe had received her own temple at the Cape of Zephyrion [I suppose this is arsinoe-aprodite-kypris-zephritis?] and, there, became the patron goddess of seafaring as Aphrodite-Arsinoe." (399)

Ptolemy II "elevated her after her death to the temple-sharing goddess of all Egyptian temples. An Egyptian goddess had now emerged from the Greek goddess Arsinoe, appearing in a completely Egyptian form on the temple reliefs and votive steles." Her cult was particular important in Memphis. She may also have a been a temple-sharing goddess in Greek temples. Isis and Aphrodite were equated, and Arsinoe was linked to them both. Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II were both temple-sharing gods for Serapis. (401)

(I had this mad plan to write a novel about Arsinoe II. Could still happen.)

___

Céline Marquaille. "The Foreign Policy of Ptolemy II". in McKechnie, Paul; Guillaume, Philippe (eds). Ptolemy II Philadelphus and his world. Leiden, Brill, 2008.

Gotta tidy away some of these photocopies randomly lying around.

Cássio de Araújo Duarte. "Scenes from the Amduat on the funerary coffins and sarcophagi of the 21st Dynasty." in Rosati, Gloria (ed). Proceedings of the Eleventh International Congress of Egyptologists. (2015: Florence, Italy) Oxford, Archaeopress Publishing, 2017.

"... the appearance of actual Amduat motifs on coffins and sarcophagi is attributed to the last years of the government of the high priest Menkheperre, and to the beginning of the 22nd Dynasty under the high priest Iput." On papyri, too. Papyri labelled "Amduat" appeared at the start of the 21st Dynasty, but their content actually came from the Litany of Re; the actual Amduat turns up on papyri "around the middle of the dynasty", with an emphasis on the last four scenes of the book.

Duarte says "the artisans were conscious of the meaning of what they were painting and, instead of producing mechanical 'copies' [of the various funerary books], they created many fascinating variations that conversed one to the other." For instance, the funeral scene in the Book of the Dead and the solar barque from the Amduat were paralleled (hoping to grab Duarte's chapter about this later in the week for more detail). Duarte points out that the interplay between these scenes combines the divine and human worlds, as well as "the last moments of decisive narratives", the conclusion of the funeral and the sun's preparation to rise. He wonders if the "sacerdotal classes" "perceived their land to bve materially populated by divine subjects and their territory to be the actual landscape of the sun god's trajectory."

He also mentions those weird diagrams where the sun falcon's head is upsidedown, and that this derives from an image in the Book of Caverns. Well stap me vitals. I'll try and post an example.

ETA, from the papyrus of Padiamun:

Also hilariously about the, erm, varying abilities of different artists: "We cannot risk idealising the scenery too much."

Onto Nut in a bit.

Nils Billing. "Text and Tomb: Some spatial properties of Nut in the Pyramid Texts." in Hawass, Zahi Abass, Brock, Lyla Pinch (eds). Egyptology at the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century: Proceedings of the Eighth International Congress of Egyptologists, Cairo, 2000. American University in Cairo Press, Cairo; New York, 2003.

There were two themes that caught my eye in this chapter. One, the importance of the reintegration of the body, in the form of the mummy. "The body disintegrated through death has been reintegrated, an ultimate precondition for rebirth." So the deceased and their parts are identified with Atum, whose name suggests tm, "complete".

The second theme is Nut as embracer and container -- analogous to the coffin that holds the mummy. Nut "extends herself over her son [Osiris/the king]": "This theme was to be repeated throughout Egyptian history in numerous variations on coffins, canopic equipment, tombs, and papyri." Nut is called "great embracer / she who embraces the Great One", "she who embraces the frightened". Billing says: "Nut represents a principle of integration. She is the all-containing waters of the sky, a celestial womb. She manifests the act of bringing together in order to give life." This role suits the "all-encompassing sky". "The dismembered pieces, themselves signs of disorder and death, are made hale and alive within her embrace." Nut is equated with the sarcophagus chamber, and the sarcophagus itself.

Alexander Piankoff. The Sky-Goddess Nut and the Night Journey of the Sun. JEA 20(1-2) 1934

Nut swallows the sun in the evening and gives birth to it in the morning: if the deceased can identify themself with the sun god, they too can rise again. Hence the goddess of the sky became "the protector of the dead, the personification of the coffin". Not surprisingly, inscriptions refer to the rebirth but seldom to the swallowing, death. (Later though, rather than not being mentioned, the West becomes the symbol of new life.) What's the geography of this journey? In the PT it's through the sky: "the dead sun was conveyed on the waters above the firmament". In later times, the creation of the universe was reenacted every morning, with the sun god rising from the waters of Nun.

"

Cássio de Araújo Duarte. "Scenes from the Amduat on the funerary coffins and sarcophagi of the 21st Dynasty." in Rosati, Gloria (ed). Proceedings of the Eleventh International Congress of Egyptologists. (2015: Florence, Italy) Oxford, Archaeopress Publishing, 2017.

"... the appearance of actual Amduat motifs on coffins and sarcophagi is attributed to the last years of the government of the high priest Menkheperre, and to the beginning of the 22nd Dynasty under the high priest Iput." On papyri, too. Papyri labelled "Amduat" appeared at the start of the 21st Dynasty, but their content actually came from the Litany of Re; the actual Amduat turns up on papyri "around the middle of the dynasty", with an emphasis on the last four scenes of the book.

Duarte says "the artisans were conscious of the meaning of what they were painting and, instead of producing mechanical 'copies' [of the various funerary books], they created many fascinating variations that conversed one to the other." For instance, the funeral scene in the Book of the Dead and the solar barque from the Amduat were paralleled (hoping to grab Duarte's chapter about this later in the week for more detail). Duarte points out that the interplay between these scenes combines the divine and human worlds, as well as "the last moments of decisive narratives", the conclusion of the funeral and the sun's preparation to rise. He wonders if the "sacerdotal classes" "perceived their land to bve materially populated by divine subjects and their territory to be the actual landscape of the sun god's trajectory."

He also mentions those weird diagrams where the sun falcon's head is upsidedown, and that this derives from an image in the Book of Caverns. Well stap me vitals. I'll try and post an example.

ETA, from the papyrus of Padiamun:

Also hilariously about the, erm, varying abilities of different artists: "We cannot risk idealising the scenery too much."

Onto Nut in a bit.

Nils Billing. "Text and Tomb: Some spatial properties of Nut in the Pyramid Texts." in Hawass, Zahi Abass, Brock, Lyla Pinch (eds). Egyptology at the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century: Proceedings of the Eighth International Congress of Egyptologists, Cairo, 2000. American University in Cairo Press, Cairo; New York, 2003.

There were two themes that caught my eye in this chapter. One, the importance of the reintegration of the body, in the form of the mummy. "The body disintegrated through death has been reintegrated, an ultimate precondition for rebirth." So the deceased and their parts are identified with Atum, whose name suggests tm, "complete".

The second theme is Nut as embracer and container -- analogous to the coffin that holds the mummy. Nut "extends herself over her son [Osiris/the king]": "This theme was to be repeated throughout Egyptian history in numerous variations on coffins, canopic equipment, tombs, and papyri." Nut is called "great embracer / she who embraces the Great One", "she who embraces the frightened". Billing says: "Nut represents a principle of integration. She is the all-containing waters of the sky, a celestial womb. She manifests the act of bringing together in order to give life." This role suits the "all-encompassing sky". "The dismembered pieces, themselves signs of disorder and death, are made hale and alive within her embrace." Nut is equated with the sarcophagus chamber, and the sarcophagus itself.

Alexander Piankoff. The Sky-Goddess Nut and the Night Journey of the Sun. JEA 20(1-2) 1934

Nut swallows the sun in the evening and gives birth to it in the morning: if the deceased can identify themself with the sun god, they too can rise again. Hence the goddess of the sky became "the protector of the dead, the personification of the coffin". Not surprisingly, inscriptions refer to the rebirth but seldom to the swallowing, death. (Later though, rather than not being mentioned, the West becomes the symbol of new life.) What's the geography of this journey? In the PT it's through the sky: "the dead sun was conveyed on the waters above the firmament". In later times, the creation of the universe was reenacted every morning, with the sun god rising from the waters of Nun.

"

A few notes. (Not a definitive summary of the book, just whatever caught my eye. Which I admit was a lot.)

(p3) The artists who worked on the 21st Dynasty funerary papyri and coffins must have worked from "artists' patterns". As often happens, that detail seemed to bring them alive in my mind's eye.

(p3-5) With some exceptions, in the New Kingdom, middle- and upper-class Egyptians and even queens could only use the Book of the Dead, while other funerary texts like Amduat and the Litany of Re were reserved for the king.

(p 7) Post-Amarna, funerary papyri started being contained in elaborate "papyrus sheaths" such as this one.

(p 8) When researchers started studying BD they thought it was like the Bible, with a standard, immutable text, so they took the best copy they could find (belonging to a Ptolemaic Egyptian named Iufankh) and divided it up into the chapters still in use. (I need to get my head around the different "redactions" / "recensions".)

(p 13) "Most of the funerary papyri begin with such a big adoration scene before a god sitting in a chapel. We will designate the initial scene, where a legend with the titles and names of the deceased and his spouse is usually encountered, with the term 'etiquette'." (Example here?) In the NK this is on the leftmost end of the scroll, in the 21D on the right.

(p 17) "Papyrus was rather expensive, and the value of a ready exemplar of the Book of the Dead... was 1 deben of silver, according to some materials from Deir el-Medina." Papyrus was sometimes reused (p76).

(p 18) Books of the Dead were pre-made and the owner's name filled in after purchase; but some were made to order, sometimes by the owner themselves, so they might have chosen which chapters and vignettes to include. (I've wondered if something similar happened with the yellow coffins.)

(p 19) In post-Amarna / Ramesside times, vignettes get bigger and better drawn, while text has more errors. (Hilariously, the start of the scroll tends to be the best-drawn, coloured, and written, which suggests only the start was shown to the customer!) Niwiński argues that the Egyptians were following a principle he calls pars pro toto -- a part for the whole -- wherein just part of the book can stand for the entire thing. So scrolls have a selection of chapters, summaries of chapters, shortened chapters, and vignettes taking the place of the text. A single spell might stand for two or even many spells. Even texts with errors, or that had been combined and no longer made sense, counted as the real thing. (This approach wasn't due to indifference or lack of ability. (p 44))

(p 32) Decorations from the BD on the tomb walls could probably substitute for a papyrus. In the 21st Dynasty, tombs were undecorated, with all the decoration going to papyri and coffins: at Thebes, "tombs of the Third Intermediate Period have the form of rock caches containing the shaft, the corridor and one or more rough chambers, the walls of which are even not smoothed." (p 35) But tomb robberies continued. "Better results were assured only through the founding of a well-protected cemetery with some huge mass tomb-caches (like Bab el-Gusus) in later years of the Dynasty." (p 37)

(p 37) For economic reasons, 21st Dynasty funerary papyri were shorter and about half as tall as their New Kingdom equivalents. (Mostly 22-25 cm high, and mostly less than 2 m long, p 74.) This made it necessary to use the pars pro toto rule to represent chapters by a fragment of text, a title, or just a vignette. The title was usually written on the back on the right-hand side (p 76).

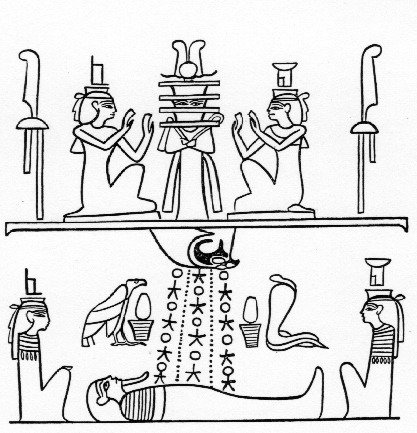

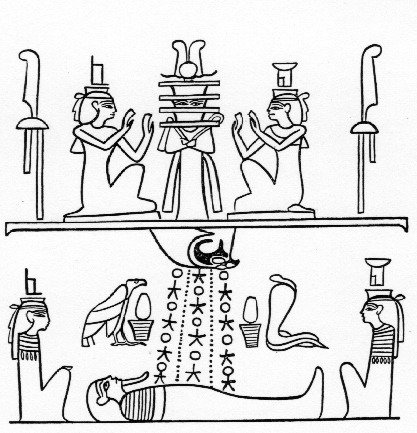

(p 38) "A series of new iconographic compositions were then created, which represented complicated conceptions of cosmogony, cosmology and eschatology by means of a limited number of figural symbols. All these scenes were an illustration of the principal theological idea of the period: the solar-Osirian unity of the aspects of the Great God, with whom the deified deceased was identified... During the travel the deceased as a form of the Sun passed through an infinite number of transformations that were at the same time understood as multiplex creations of Osiris 'with many faces' (ꜥš3 ḥrw) , or 'with many forms' (ꜥš3 ḫprw) , or else 'with many names' (ꜥš3 rnw)". The idea of Osiris with many forms, and an eternal journey with the sun, reflects the contents of the Litany of Re and other books. Papyri didn't have enough room to hold all of this; so the inner coffins were covered in vignette. (Outer coffins continued to be decorated with traditional motifs (p 42).

(p 39) The new scene included

-- Shu lifting Nut

-- Osiris on the Double Staircase protected by the Great Serpent

-- the solar barque above chopped-up Apophis

-- the Sycamore Goddess

-- the Cosmic Cow going forth from the Western Mountain

(p 42) "Since the early years of the Dynasty, until at least the middle of the 9th century B.C. each typical funerary ensemble comprised two papyri: the BD-manuscript in the papyrus-sheath, and the 'Amduat' -papyrus bandaged together with the mummy, usually placed between its legs." The need for two papyri per burial meant an increase in the number of workshops. Some of the workers were better than others, and some clients might have been able to pay for better quality products than others. They worked from many different patterns of the texts and pictures. (p 43)

The papyri are very various, in size, length, and content.

(p 44) "some papyri entitled pry m hrw do not resemble the Book of the Dead of the New Kingdom at all... often one finds himself faced with quite new texts and scenes without any analogy."

(p 45) "There are coloured papyri with their vignettes painted red, white, blue, green, brown, pink and even gilded ones, and the figures and some other papyri of the same period are only outlined in black." Some are mostly text; some are almost entirely pictures.

(p 71) After a discussion of the history of the study of the papyri, Niwiński concludes we should drop "mythological papyri" as a third category (after Book of the Dead and Amduat). Not sure I follow this yet.

(p 77) For some papyri, such as those depicting the BD or the Amduat, the artist didn't have a lot of choice about content. But they did control some details, such as the border decoration.

(p 93) The texts on the papyri fall into these groups: (a) BD excerpts, (b) hymns and "litany-like incantations" illustrated by "the Great God in his different forms": Osiris, Re, the door guardians, the judges; (c) Amduat excerpts; (d) excerpts from the Books of the Underworld (the Book of Gates, Book of Caverns, Book of the Earth, etc); (e) offering formulas.

(p 95) The illustrations fall into these groups: (a) BD vignettes; (b) illustrations to hymns and litanies; (c) Amduat illustrations; (d) Books of the Underworld illustrations; (e) the original 21st Dynasty images.

(Never seen the door guardians and the judges of the weighing of the heart referred to as aspects of Osiris-Re before, though I suppose it makes sense!)

(p 97) Most papyri included an "etiquette", a large opening vignette with the deceased's name and titles, often with a portrait of the deceased worshipping a god (most often Osiris (p99)). (Here's Pinedjem II's, which includes no other illustrations. And here's Maatkare's, with the God's Wife depicted as a divinity herself, receiving offerings.)

(p 105) Papyri which were given a title might be entitled the Book of Coming Forth by Day (ie the Book of the Dead), or the Amduat. Book of the Dead papyri included those where images take up 90% of the decorated space, including the newly devised images, which don't illustrate BD chapters. Niwiński calls these "the new redaction of the 21st Dynasty (p 123). (There are also new images added to the traditional Book of the Dead illustrations, such as Amentet with a hieroglyphic head and the mouse-headed god who holds a hand to his snout. (p 123).

This way to part two of my notes!

___

Andrzej Niwiński. Studies on the Illustrated Theban Funerary Papyri of the 11th and 10th Centuries BC. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 86. Göttingen, Vandenhoeck u. Ruprecht, 1989.

(p3) The artists who worked on the 21st Dynasty funerary papyri and coffins must have worked from "artists' patterns". As often happens, that detail seemed to bring them alive in my mind's eye.

(p3-5) With some exceptions, in the New Kingdom, middle- and upper-class Egyptians and even queens could only use the Book of the Dead, while other funerary texts like Amduat and the Litany of Re were reserved for the king.

(p 7) Post-Amarna, funerary papyri started being contained in elaborate "papyrus sheaths" such as this one.

(p 8) When researchers started studying BD they thought it was like the Bible, with a standard, immutable text, so they took the best copy they could find (belonging to a Ptolemaic Egyptian named Iufankh) and divided it up into the chapters still in use. (I need to get my head around the different "redactions" / "recensions".)

(p 13) "Most of the funerary papyri begin with such a big adoration scene before a god sitting in a chapel. We will designate the initial scene, where a legend with the titles and names of the deceased and his spouse is usually encountered, with the term 'etiquette'." (Example here?) In the NK this is on the leftmost end of the scroll, in the 21D on the right.

(p 17) "Papyrus was rather expensive, and the value of a ready exemplar of the Book of the Dead... was 1 deben of silver, according to some materials from Deir el-Medina." Papyrus was sometimes reused (p76).

(p 18) Books of the Dead were pre-made and the owner's name filled in after purchase; but some were made to order, sometimes by the owner themselves, so they might have chosen which chapters and vignettes to include. (I've wondered if something similar happened with the yellow coffins.)

(p 19) In post-Amarna / Ramesside times, vignettes get bigger and better drawn, while text has more errors. (Hilariously, the start of the scroll tends to be the best-drawn, coloured, and written, which suggests only the start was shown to the customer!) Niwiński argues that the Egyptians were following a principle he calls pars pro toto -- a part for the whole -- wherein just part of the book can stand for the entire thing. So scrolls have a selection of chapters, summaries of chapters, shortened chapters, and vignettes taking the place of the text. A single spell might stand for two or even many spells. Even texts with errors, or that had been combined and no longer made sense, counted as the real thing. (This approach wasn't due to indifference or lack of ability. (p 44))

(p 32) Decorations from the BD on the tomb walls could probably substitute for a papyrus. In the 21st Dynasty, tombs were undecorated, with all the decoration going to papyri and coffins: at Thebes, "tombs of the Third Intermediate Period have the form of rock caches containing the shaft, the corridor and one or more rough chambers, the walls of which are even not smoothed." (p 35) But tomb robberies continued. "Better results were assured only through the founding of a well-protected cemetery with some huge mass tomb-caches (like Bab el-Gusus) in later years of the Dynasty." (p 37)

(p 37) For economic reasons, 21st Dynasty funerary papyri were shorter and about half as tall as their New Kingdom equivalents. (Mostly 22-25 cm high, and mostly less than 2 m long, p 74.) This made it necessary to use the pars pro toto rule to represent chapters by a fragment of text, a title, or just a vignette. The title was usually written on the back on the right-hand side (p 76).

(p 38) "A series of new iconographic compositions were then created, which represented complicated conceptions of cosmogony, cosmology and eschatology by means of a limited number of figural symbols. All these scenes were an illustration of the principal theological idea of the period: the solar-Osirian unity of the aspects of the Great God, with whom the deified deceased was identified... During the travel the deceased as a form of the Sun passed through an infinite number of transformations that were at the same time understood as multiplex creations of Osiris 'with many faces' (ꜥš3 ḥrw) , or 'with many forms' (ꜥš3 ḫprw) , or else 'with many names' (ꜥš3 rnw)". The idea of Osiris with many forms, and an eternal journey with the sun, reflects the contents of the Litany of Re and other books. Papyri didn't have enough room to hold all of this; so the inner coffins were covered in vignette. (Outer coffins continued to be decorated with traditional motifs (p 42).

(p 39) The new scene included

-- Shu lifting Nut

-- Osiris on the Double Staircase protected by the Great Serpent

-- the solar barque above chopped-up Apophis

-- the Sycamore Goddess

-- the Cosmic Cow going forth from the Western Mountain

(p 42) "Since the early years of the Dynasty, until at least the middle of the 9th century B.C. each typical funerary ensemble comprised two papyri: the BD-manuscript in the papyrus-sheath, and the 'Amduat' -papyrus bandaged together with the mummy, usually placed between its legs." The need for two papyri per burial meant an increase in the number of workshops. Some of the workers were better than others, and some clients might have been able to pay for better quality products than others. They worked from many different patterns of the texts and pictures. (p 43)

The papyri are very various, in size, length, and content.

(p 44) "some papyri entitled pry m hrw do not resemble the Book of the Dead of the New Kingdom at all... often one finds himself faced with quite new texts and scenes without any analogy."

(p 45) "There are coloured papyri with their vignettes painted red, white, blue, green, brown, pink and even gilded ones, and the figures and some other papyri of the same period are only outlined in black." Some are mostly text; some are almost entirely pictures.

(p 71) After a discussion of the history of the study of the papyri, Niwiński concludes we should drop "mythological papyri" as a third category (after Book of the Dead and Amduat). Not sure I follow this yet.

(p 77) For some papyri, such as those depicting the BD or the Amduat, the artist didn't have a lot of choice about content. But they did control some details, such as the border decoration.

(p 93) The texts on the papyri fall into these groups: (a) BD excerpts, (b) hymns and "litany-like incantations" illustrated by "the Great God in his different forms": Osiris, Re, the door guardians, the judges; (c) Amduat excerpts; (d) excerpts from the Books of the Underworld (the Book of Gates, Book of Caverns, Book of the Earth, etc); (e) offering formulas.

(p 95) The illustrations fall into these groups: (a) BD vignettes; (b) illustrations to hymns and litanies; (c) Amduat illustrations; (d) Books of the Underworld illustrations; (e) the original 21st Dynasty images.

(Never seen the door guardians and the judges of the weighing of the heart referred to as aspects of Osiris-Re before, though I suppose it makes sense!)

(p 97) Most papyri included an "etiquette", a large opening vignette with the deceased's name and titles, often with a portrait of the deceased worshipping a god (most often Osiris (p99)). (Here's Pinedjem II's, which includes no other illustrations. And here's Maatkare's, with the God's Wife depicted as a divinity herself, receiving offerings.)

(p 105) Papyri which were given a title might be entitled the Book of Coming Forth by Day (ie the Book of the Dead), or the Amduat. Book of the Dead papyri included those where images take up 90% of the decorated space, including the newly devised images, which don't illustrate BD chapters. Niwiński calls these "the new redaction of the 21st Dynasty (p 123). (There are also new images added to the traditional Book of the Dead illustrations, such as Amentet with a hieroglyphic head and the mouse-headed god who holds a hand to his snout. (p 123).

This way to part two of my notes!

___

Andrzej Niwiński. Studies on the Illustrated Theban Funerary Papyri of the 11th and 10th Centuries BC. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 86. Göttingen, Vandenhoeck u. Ruprecht, 1989.

Links October 2023

Oct. 27th, 2023 01:03 pm'Cyber-archaeology' salvages lost Iraqi art (BBC, 2015)

Middle Egyptian Grammar by Dr. Gabor Toth -- texts, vocabulary, exercises, etc

Volcanic eruptions may have contributed to war in ancient Egypt (SMH, 2017)

Viking expert raises doubts over research claiming famous warrior was actually a woman (ABC, 2017)

Egypt had an unusually powerful 'female king' 5,000 years ago, lavish tomb suggests (Livescience, October 2023). Meret-Neith, wife of the First Dynasty pharaoh Djet. It's not clear if she reigned in her own right.

Ancient Egyptian papyrus describes dozens of venomous snakes, including rare 4-fanged serpent (Livescience, October 2023).

4,500-year-old Sumerian temple dedicated to mighty thunder god discovered in Iraq (Livescience, February 2023). The god in question is Ningirsu.

Falcon shrine with cryptic message unearthed in Egypt baffles archaeologists (Livescience, October 2022). "An ancient falcon shine in Berenike, an old port city in Egypt, has flummoxed archaeologists who aren't sure what to make of its headless falcons, unknown gods and cryptic message that reads, 'It is improper to boil a head in here.'"

500 Year-Old Love Letter Found Buried with Korean Mummy (IBT, 2013)

Ancient Viking warrior given a hero’s burial may have actually been ‘transgender, non-binary or gender fluid’, researchers say (Pink News, 2020) | Archaeologists say it’s not scientific to assume gender of ancient human remains (Pink News, 2022) -- not just gender, but sex, which can't always be accurately determined and may not dictate how someone lived, which is why there are multiple "Oops! Warrior was not a man!" news stories | 1,000-year-old skeleton may have been non-binary medieval warrior, say archaeologists (Pink News, 2021)

The Theory That Men Evolved to Hunt and Women Evolved to Gather Is Wrong (Sci Am, November 2023) | Worldwide survey kills the myth of ‘Man the Hunter’ (Science, June 2023)

Lost Ethiopian town comes from an ancient empire that rivalled Rome (NS, 2020) ie Aksum

Oldest legible sentence written with first alphabet is about head lice (NS, 2022)

Where was the first city in the world? (NS, nd)

Powerful photo by Pacific Indigenous artist reveals truth about 1899 painting (CNN, 2022). "Kihara also believes that Gauguin’s models may not be cisgender women, referencing the research of Māori scholar Dr. Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, who has written that the “androgynous” models he painted were likely Māhū – the Indigenous Polynesian community that, like Samoa’s Faʻafafine, are considered to be a third gender and express a female identity."

Egypt unearths 'world's oldest' mass-production brewery, dating back to era of King Narmer, more than 5,000 years ago (ABC, 2021)

Third Gender: An Entrancing Look at Mexico's Muxes (YouTube, 2017)

The Hidden Girls of Afghanistan (YouTube, 2017) | Inside the Lives of Girls Dressed as Boys in Afghanistan (NG, 2018) | I'm a Woman Who Lived as a Boy: My Years as a Bacha Posh (Time, 2014) | Bacha Posh: An Afghan social tradition where girls are raised as boys (The News Minute, 2018) | She is My Son Afghanistan's Bacha Posh, When Girls Become Boys (YouTube, 2018)

Did Aboriginal and Asian people trade before European settlement in Darwin? (ABC, 2018)

History of chocolate rewritten by cacao traces found on ancient pottery unearthed in Ecuador (ABC, 2018)

Earliest roasted root vegetables found in 170,000-year-old cave dirt (NS, 2020)

Religion from nature, not archaeology (Starhawk, 2001). Still an important document.

Middle Egyptian Grammar by Dr. Gabor Toth -- texts, vocabulary, exercises, etc

Volcanic eruptions may have contributed to war in ancient Egypt (SMH, 2017)

Viking expert raises doubts over research claiming famous warrior was actually a woman (ABC, 2017)

Egypt had an unusually powerful 'female king' 5,000 years ago, lavish tomb suggests (Livescience, October 2023). Meret-Neith, wife of the First Dynasty pharaoh Djet. It's not clear if she reigned in her own right.

Ancient Egyptian papyrus describes dozens of venomous snakes, including rare 4-fanged serpent (Livescience, October 2023).

4,500-year-old Sumerian temple dedicated to mighty thunder god discovered in Iraq (Livescience, February 2023). The god in question is Ningirsu.

Falcon shrine with cryptic message unearthed in Egypt baffles archaeologists (Livescience, October 2022). "An ancient falcon shine in Berenike, an old port city in Egypt, has flummoxed archaeologists who aren't sure what to make of its headless falcons, unknown gods and cryptic message that reads, 'It is improper to boil a head in here.'"

500 Year-Old Love Letter Found Buried with Korean Mummy (IBT, 2013)

Ancient Viking warrior given a hero’s burial may have actually been ‘transgender, non-binary or gender fluid’, researchers say (Pink News, 2020) | Archaeologists say it’s not scientific to assume gender of ancient human remains (Pink News, 2022) -- not just gender, but sex, which can't always be accurately determined and may not dictate how someone lived, which is why there are multiple "Oops! Warrior was not a man!" news stories | 1,000-year-old skeleton may have been non-binary medieval warrior, say archaeologists (Pink News, 2021)

The Theory That Men Evolved to Hunt and Women Evolved to Gather Is Wrong (Sci Am, November 2023) | Worldwide survey kills the myth of ‘Man the Hunter’ (Science, June 2023)

Lost Ethiopian town comes from an ancient empire that rivalled Rome (NS, 2020) ie Aksum

Oldest legible sentence written with first alphabet is about head lice (NS, 2022)

Where was the first city in the world? (NS, nd)

Powerful photo by Pacific Indigenous artist reveals truth about 1899 painting (CNN, 2022). "Kihara also believes that Gauguin’s models may not be cisgender women, referencing the research of Māori scholar Dr. Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, who has written that the “androgynous” models he painted were likely Māhū – the Indigenous Polynesian community that, like Samoa’s Faʻafafine, are considered to be a third gender and express a female identity."

Egypt unearths 'world's oldest' mass-production brewery, dating back to era of King Narmer, more than 5,000 years ago (ABC, 2021)

Third Gender: An Entrancing Look at Mexico's Muxes (YouTube, 2017)

The Hidden Girls of Afghanistan (YouTube, 2017) | Inside the Lives of Girls Dressed as Boys in Afghanistan (NG, 2018) | I'm a Woman Who Lived as a Boy: My Years as a Bacha Posh (Time, 2014) | Bacha Posh: An Afghan social tradition where girls are raised as boys (The News Minute, 2018) | She is My Son Afghanistan's Bacha Posh, When Girls Become Boys (YouTube, 2018)

Did Aboriginal and Asian people trade before European settlement in Darwin? (ABC, 2018)

History of chocolate rewritten by cacao traces found on ancient pottery unearthed in Ecuador (ABC, 2018)

Earliest roasted root vegetables found in 170,000-year-old cave dirt (NS, 2020)

Religion from nature, not archaeology (Starhawk, 2001). Still an important document.

The Gentleman

Oct. 11th, 2023 05:21 pmWhile obsessing over Hepet-Hor on 21st Dynasty yellow coffins, I noticed another figure whom I nicknamed "the Gentleman". He is a mummiform, snake-headed demon, with a crown or feather and a beard. Now, I was just reading The Greenfield Papyrus by Budge and its description of Hepet-Hor on Plate CVIII: "[she] is sometimes represented wearing a beard and a crown, consisting of the White Crown to which are added plumes, a disk, and horizontal twisted horns, above which rise uraei wearing horns with disks between them." That's the Gentleman! Could he be she?

The Gentleman appears on coffin fragment 87.4-E at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, in exactly the position you'd expect to see Hepet-Hor -- guarding Osiris on his Mound. Did appearances like this inspire Budge's comment, or is the Gentleman sometimes actually labelled with Hepet-Hor's name? (Where's my photocopy from the Lexikon?) On this coffin, according to Éva Liptay, the figure is labelled "imAxy xr nTr aA" -- "honoured by the great god".

My investigations continue!

__

E.A. Wallis Budge. The Greenfield Papyrus. British Museum, London, 1912.

Raymond O. Faulkner. A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian. Griffith Institute, Oxford, 1962.

Éva Liptay. Coffins and Coffin Fragments of the Third Intermediate Period. The Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, 2011.

The Gentleman appears on coffin fragment 87.4-E at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, in exactly the position you'd expect to see Hepet-Hor -- guarding Osiris on his Mound. Did appearances like this inspire Budge's comment, or is the Gentleman sometimes actually labelled with Hepet-Hor's name? (Where's my photocopy from the Lexikon?) On this coffin, according to Éva Liptay, the figure is labelled "imAxy xr nTr aA" -- "honoured by the great god".

My investigations continue!

__

E.A. Wallis Budge. The Greenfield Papyrus. British Museum, London, 1912.

Raymond O. Faulkner. A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian. Griffith Institute, Oxford, 1962.

Éva Liptay. Coffins and Coffin Fragments of the Third Intermediate Period. The Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, 2011.