A few notes. (Not a definitive summary of the book, just whatever caught my eye. Which I admit was a lot.)

(p3) The artists who worked on the 21st Dynasty funerary papyri and coffins must have worked from "artists' patterns". As often happens, that detail seemed to bring them alive in my mind's eye.

(p3-5) With some exceptions, in the New Kingdom, middle- and upper-class Egyptians and even queens could only use the Book of the Dead, while other funerary texts like Amduat and the Litany of Re were reserved for the king.

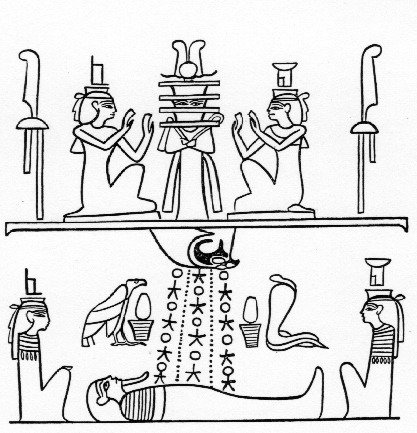

(p 7) Post-Amarna, funerary papyri started being contained in elaborate "papyrus sheaths" such as

this one.

(p 8) When researchers started studying BD they thought it was like the Bible, with a standard, immutable text, so they took the best copy they could find (belonging to a Ptolemaic Egyptian named Iufankh) and divided it up into the chapters still in use. (I need to get my head around the different "redactions" / "recensions".)

(p 13) "Most of the funerary papyri begin with such a big adoration scene before a god sitting in a chapel. We will designate the initial scene, where a legend with the titles and names of the deceased and his spouse is usually encountered, with the term 'etiquette'." (Example

here?) In the NK this is on the leftmost end of the scroll, in the 21D on the right.

(p 17) "Papyrus was rather expensive, and the value of a ready exemplar of the Book of the Dead... was 1 deben of silver, according to some materials from Deir el-Medina." Papyrus was sometimes reused (p76).

(p 18) Books of the Dead were pre-made and the owner's name filled in after purchase; but some were made to order, sometimes by the owner themselves, so they might have chosen which chapters and vignettes to include. (I've wondered if something similar happened with the yellow coffins.)

(p 19) In post-Amarna / Ramesside times, vignettes get bigger and better drawn, while text has more errors. (Hilariously, the start of the scroll tends to be the best-drawn, coloured, and written, which suggests only the start was shown to the customer!) Niwi

ński argues that the Egyptians were following a principle he calls

pars pro toto -- a part for the whole -- wherein just part of the book can stand for the entire thing. So scrolls have a selection of chapters, summaries of chapters, shortened chapters, and vignettes taking the place of the text. A single spell might stand for two or even many spells. Even texts with errors, or that had been combined and no longer made sense, counted as the real thing. (This approach wasn't due to indifference or lack of ability. (p 44))

(p 32) Decorations from the BD on the tomb walls could probably substitute for a papyrus. In the 21st Dynasty, tombs were undecorated, with all the decoration going to papyri and coffins: at Thebes, "tombs of the Third Intermediate Period have the form of rock caches containing the shaft, the corridor and one or more rough chambers, the walls of which are even not smoothed." (p 35) But tomb robberies continued. "Better results were assured only through the founding of a well-protected cemetery with some huge mass tomb-caches (like Bab el-Gusus) in later years of the Dynasty." (p 37)

(p 37) For economic reasons, 21st Dynasty funerary papyri were shorter and about half as tall as their New Kingdom equivalents. (Mostly 22-25 cm high, and mostly less than 2 m long, p 74.) This made it necessary to use the

pars pro toto rule to represent chapters by a fragment of text, a title, or just a vignette. The title was usually written on the back on the right-hand side (p 76).

(p 38) "A series of new iconographic compositions were then created, which represented complicated conceptions of cosmogony, cosmology and eschatology by means of a limited number of figural symbols. All these scenes were an illustration of the principal theological idea of the period: the solar-Osirian unity of the aspects of the Great God, with whom the deified deceased was identified... During the travel the deceased as a form of the Sun passed through an infinite number of transformations that were at the same time understood as multiplex creations of Osiris 'with many faces' (

ꜥš3 ḥrw) , or 'with many forms' (

ꜥš3 ḫprw) , or else 'with many names' (

ꜥš3 rnw)". The idea of Osiris with many forms, and an eternal journey with the sun, reflects the contents of the Litany of Re and other books. Papyri didn't have enough room to hold all of this; so the inner coffins were covered in vignette. (Outer coffins continued to be decorated with traditional motifs (p 42).

(p 39) The new scene included

-- Shu lifting Nut

-- Osiris on the Double Staircase protected by the Great Serpent

-- the solar barque above chopped-up Apophis

-- the Sycamore Goddess

-- the Cosmic Cow going forth from the Western Mountain

(p 42) "Since the early years of the Dynasty, until at least the middle of the 9th century B.C. each typical funerary ensemble comprised two papyri: the BD-manuscript in the papyrus-sheath, and the 'Amduat' -papyrus bandaged together with the mummy, usually placed between its legs." The need for two papyri per burial meant an increase in the number of workshops. Some of the workers were better than others, and some clients might have been able to pay for better quality products than others. They worked from many different patterns of the texts and pictures. (p 43)

The papyri are very various, in size, length, and content.

(p 44) "some papyri entitled pry m hrw do not resemble the Book of the Dead of the New Kingdom at all... often one finds himself faced with quite new texts and scenes without any analogy."

(p 45) "There are coloured papyri with their vignettes painted red, white, blue, green, brown, pink and even gilded ones, and the figures and some other papyri of the same period are only outlined in black." Some are mostly text; some are almost entirely pictures.

(p 71) After a discussion of the history of the study of the papyri, Niwi

ński concludes we should drop "mythological papyri" as a third category (after Book of the Dead and Amduat). Not sure I follow this yet.

(p 77) For some papyri, such as those depicting the BD or the Amduat, the artist didn't have a lot of choice about content. But they did control some details, such as the border decoration.

(p 93) The texts on the papyri fall into these groups: (a) BD excerpts, (b) hymns and "litany-like incantations" illustrated by "the Great God in his different forms": Osiris, Re, the door guardians, the judges; (c) Amduat excerpts; (d) excerpts from the Books of the Underworld (the Book of Gates, Book of Caverns, Book of the Earth, etc); (e) offering formulas.

(p 95) The illustrations fall into these groups: (a) BD vignettes; (b) illustrations to hymns and litanies; (c) Amduat illustrations; (d) Books of the Underworld illustrations; (e) the original 21st Dynasty images.

(Never seen the door guardians and the judges of the weighing of the heart referred to as aspects of Osiris-Re before, though I suppose it makes sense!)

(p 97) Most papyri included an "etiquette", a large opening vignette with the deceased's name and titles, often with a portrait of the deceased worshipping a god (most often Osiris (p99)). (Here's

Pinedjem II's, which includes no other illustrations. And here's

Maatkare's, with the God's Wife depicted as a divinity herself, receiving offerings.)

(p 105) Papyri which were given a title might be entitled the Book of Coming Forth by Day (ie the Book of the Dead), or the Amduat. Book of the Dead papyri included those where images take up 90% of the decorated space, including the newly devised images, which don't illustrate BD chapters. Niwi

ński calls these "the new redaction of the 21st Dynasty (p 123). (There are also new images added to the traditional Book of the Dead illustrations, such as Amentet with a hieroglyphic head and the mouse-headed god who holds a hand to his snout. (p 123).

This way to

part two of my notes!

___

Andrzej Niwi

ński.

Studies on the Illustrated Theban Funerary Papyri of the 11th and 10th Centuries BC. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 86. Göttingen, Vandenhoeck u. Ruprecht, 1989.